The Difference Between Gain, Volume, Level, and Loudness

Last Updated on June 29, 2024 by Datatoys

This article originally appeared at http://www.offbeatband.com/2009/08/the-difference-between-gain-volume-level-and-loudness/

When working with sound amplification equipment, we often misuse these terms. Probably because you’ll see them often, and two or three on the same piece of equipment! That can seriously make your brain want to go flip upside-down and jump into a pool of boiling acoustic particle velocity soup. On top of that, you might have channel volume, master volume, guitar volume, fader levels, guitar amp gain, mixer board gain … etc. But, it’s pretty important stuff to understand if you want to get a good sound from your equipment.

Gain

Gain is one of the harder terms to define, mainly because its used in a lot more places than just the audio world. Quite simply it means an increase in some kind of value. So for example, you can have a power gain, voltage gain, or current gain; and they all increase those respective values. Typically when referring to gain, we refer to transmission gain, which is the increase in the power of the signal. This increase is almost always expressed in dB (decibels). This could be the increase in the raw signal from your guitar or microphone before it goes into any of the other electronic components. For the curious, here’s the equation to calculate gain:

Gain = 10 x log (Power out/Power in)

expressed in dB.

Practical Use of Gain

For all non-rocket scientist purposes, you’re probably going to see a gain control in two places. One of them is on your mixer board or PA, and the other is on a guitar amp. These both mean the same thing as far as electronics go, but serve different purposes in each.

On the mixer board, you’ll see the gain at the top of the board. It’s the first control that the raw mic signal sees, and it will boost the signal to a sufficient level for the rest of the controls to work properly. You’ll want to set this gain level high enough to bring up the level of the signal, but not so high that you’ll get clipping or distortion in the signal. For this purpose, many boards come with a PFL (Pre-Fader Listen) button. This button will let you see the actual signal strength by looking at the LEDs on the board. Use the mic at normal sound levels and set the gain knob so that the peaks in sound don’t send the signal into the red, and you’re good to go.

On a guitar amp, the gain’s main intention is to create distortion (as my blood tingles with ground shaking delight). You already know what it does, so there’s no point in telling you, but I do have a small tip – turn your gain down! Yes, I also love the gut wrenching melodies of face-meltifying solos, but you seriously don’t need your gain sitting on 10 all the time. Novices will go into the recording studio thinking their sound is redonkulously awesome, only to have the sound engineer take their distortion down to a 5 or 6 cause they sound terrible. The distortion shouldn’t hide your skills, but accentuate them.

Volume

Besides defining three dimensional space, volume can also be used to describe the power level of a signal. So when you turn up the “master volume” knob on your amp, it simply means you’re increasing the amount of power used by the amp to increase the signal. This term is quite ambiguous since it’s used in so many different places, mainly to mean the actual sound you perceive in your ears, which is not exactly true. Use with caution.

Level

This term is used to describe the magnitude of the sound in reference to some arbitrary reference. More specifically we use SPL (sound pressure level) to describe sound waves. SPL is a term calculated from the log of the rms sound pressure of a measured sound related to a reference value. Basically meaning we create a measurement scale with zero starting at the lowest threshold of human hearing. The SPL scale is shown in dB and goes up to 130 dB (well, infinity, but whatever), which is the threshold of pain for the human ear. Now I just need to find a way to rock as loud as Krakatoa (180 dB standing 100 miles away).

Loudness

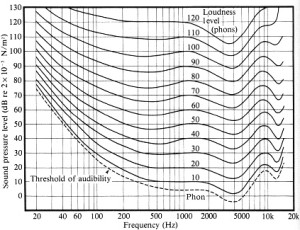

Loudness, even though similar to volume and level, is another monster. Since human ears are not able to hear each frequency at the same level, perceived loudness is different as we move up and down in frequency. The following graph shows the level that a human ear “thinks” its hearing, which as you can see is not correct most of the time. The lower frequencies, like the bass guitar at 40-220 Hz, need more sound pressure for us to believe it’s equally as loud as a sound at 1 kHz.

Source: http://www.offbeatband.com/2009/08/the-difference-between-gain-volume-level-and-loudness/

Equal Loudness Contours

Here we introduce a term called a “phon“, which is used to describe loudness. You can see on the graph that the phon contour is different for each dB level. The 120 phon contour requires less boost in the low frequencies than the 10 phon contour. Mostly because of the shape of the ear, you can also see from the graph that we hear the 3-4 kHz range the best, which happens to be on the slightly higher end of human speech. If you lost it, you’d have a hard time understanding people.

Source: http://www.offbeatband.com/2009/08/the-difference-between-gain-volume-level-and-loudness/

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!